The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving

Title : The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving

Link : The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving

Most schoolchildren are taught that Squanto was a friendly native who saved the Pilgrims, but the truth is much more complex.

Tisquantum, colloquially known as “Squanto,” was of the Patuxet tribe in Massachusetts. He escaped the clutches of slavery from an English explorer and acted as liaison to the first pilgrims in Massachusetts, but Squanto also used his unique relationship with the settlers and his grasp of the English language in his personal pursuit of power.

Squanto’s Early Life And Kidnapping

Historians generally agree that Squanto belonged to the Patuxet tribe which was a branch of the Wampanoag Confederacy and lived around Plymouth. The men of the tribe would often travel up and down the coast on fishing expeditions while the women cultivated corn, beans, and squash. The Patuxet first came into contact with the Europeans under friendly relations, but they would eventually be annihilated in the early 1600s.

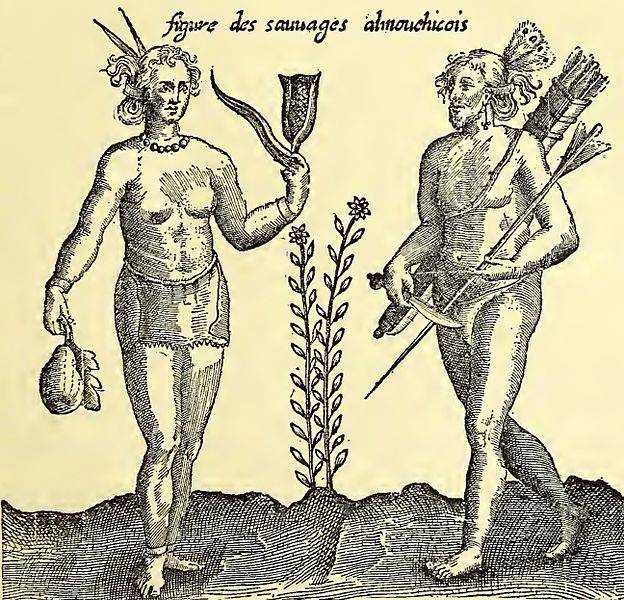

A French 1612 depiction of the New England “savages.”

At some point during his youth, Squanto was captured by the English and taken to Europe as a slave. The most widely-accept theory is that Squanto and 23 other Native Americans came on board the ship of Captain Thomas Hunt, who was lieutenant to the more famous Captain John Smith, who put them at ease with promises of trade before setting sail for the open ocean with the Natives held captive aboard.

The Patuxet were outraged by the kidnappings but there was nothing they could do: the English and their prisoners were long gone, and the remaining Patuxet would be wiped out by smallpox.

Squanto and the others were sold by Hunt as slaves in Spain, although Squanto somehow managed to escape to England where he mastered the language. Mayflower pilgrim William Bradford, who did actually get to know Squanto very well years later, wrote: “he got away for England, and was entertained by a merchant in London, employed to Newfoundland and other parts.”

It was in Newfoundland that Squanto met Captain Thomas Dermer, a man in the employ of Sir Ferdinando Gorges, an Englishman who helped found “the Province of Maine” back on Squanto’s home continent.

In 1619 Gorges sent Dermer on a trade mission to the New England colonies and employed Squanto as an interpreter.

As Squanto’s ship approached the coast, Dermer noted how they observed “some ancient [Indian] plantations, not long since populous now utterly void.” Squanto’s tribe had been annihilated by the smallpox plague the white men had brought with them.

Then, in 1620, Dermer and his crew were set upon by the Wampanoag tribe near modern Martha’s Vineyard and slaughtered. Dermer and 14 men managed to escape and Squanto was taken captive by the tribe.

The Pilgrims

In early 1621, Squanto found himself still a prisoner of the Wampanoag, who cautiously observed a group of new English arrivals from a few months prior in November of the previous year. These Europeans had suffered grievously in the New England winter but the Wampanoag were still hesitant to approach them, given that in the past Natives who attempted to befriend the English had been taken on board their ships and never seen again.

A statue of Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoag, in Plymouth.

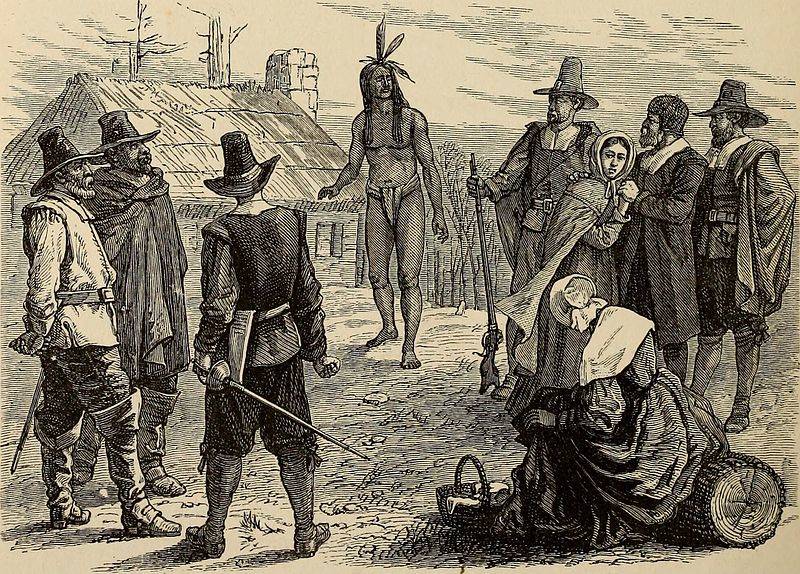

Eventually, however, as Bradford records, a Wampanoag name Samoset “came boldly amongst [a group of pilgrims pilgrims] and spoke to them in broken English, which they could well understand but marveled at it.”

Samoset made conversation with the pilgrims for a while before explaining there was another man “whose name was Squanto, a native of this place, who had been in England and could speak better English than himself.”

The Pilgrims were astounded when Samoset approached them and addressed them in English.

If they had been surprised by Samoset’s command of English, the Pilgrims must have been shocked beyond belief by Squanto’s mastery of the language, which would prove to be a great blessing to both parties. With the assistance of Squanto as interpreter, the Wampanoag chief Massasoit negotiated an alliance with the Pilgrims and promised not to harm each other. He also promised that they would aid each other in the event of an attack from another tribe.

Bradford described Squanto as “a special instrument sent of God.”

Thanksgiving And Squanto’s Death

Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to cultivate crops that would help them to get through the next winter. The Pilgrims were delighted to find that the corn and squash were easy to grow in the Massachusetts climate.

As an expression of their gratitude, they invited Squanto and around 90 Wampanoag to join them in a feast celebrating their first successful harvest in the New World. But the real-life Squanto differed quite a bit from the way he is portrayed in elementary school textbooks about his role with the pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving.

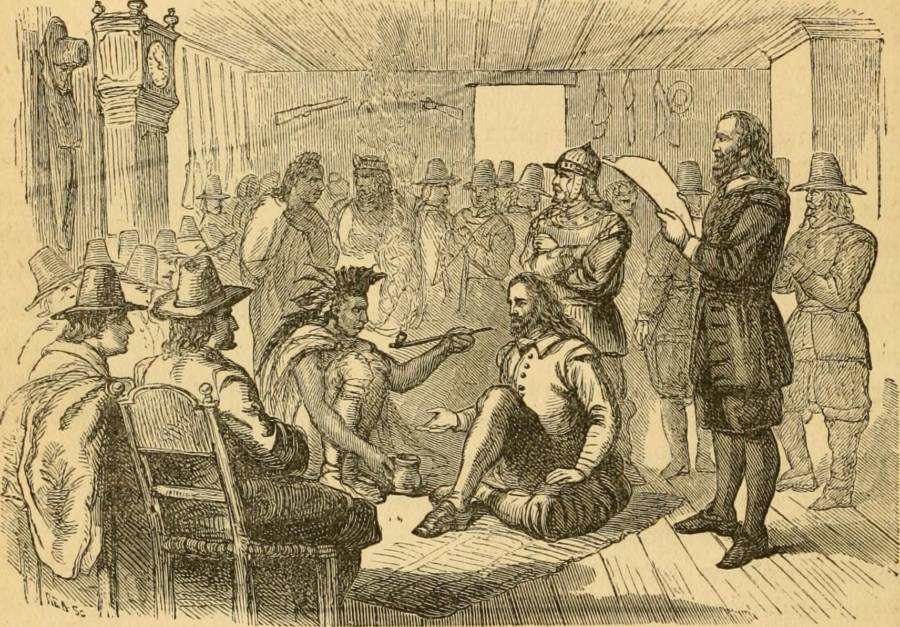

With the help of Squanto, the Wampanoag and Pilgrims negotiated a fairly stable peace.

While the pilgrims doubtless could not have survived without Squanto’s help, the Patuxet’s motives may have had less to do with good-heartedness than securing his own position.

Squanto knew that he would become invaluable to the Wampanoag once he established himself as the pilgrim’s closest ally. It’s easy to imagine that he would want his revenge on the people who enslaved him and he soon began “to persuade the Indians [that] he could lead us to peace or war at his pleasure.” Squanto would exploit the power his command of English had given him by threatening individuals who displeased him and demanded favors in return for appeasing the pilgrims.

William Bradford befriended Squanto and later saved him from his own people.

Squanto, at last, overstepped his bounds and enraged the Wampanoag by claiming that Chief Massosoit had been plotting with enemy tribes, a lie that was quickly exposed. He was forced to take shelter with the Pilgrims who, although they had also become wary of him, refused to betray their former ally by handing him over to certain death among the natives.

It proved not to matter, as in November 1622, Squanto succumbed to a fatal disease. He died within a few days of asking “Governor [Bradford] to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen’s God in heaven.”

The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving

Enough news articles The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving this time, hopefully can benefit for you all. Well, see you in other article postings.

The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving

You are now reading the article The True Story Of The Native American Behind The First Thanksgiving with the link address https://randomfindtruth.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-true-story-of-native-american.html